Two years in Camp Amache: Joe Kamiya’s story

The author’s father recalls his and his family’s internment during World War II.

Joe Kamiya returns to Camp Amache in July 2008, 64 years after he and his family were interned there.

In the previous story, my father, Joe Kamiya, described how his dream of becoming a chicken czar ended when all Japanese-Americans on the West Coast were ordered into prison camps. This story, taken from an interview conducted by me (with input from Joe’s wife Joanne Kamiya) on Sept. 26, 2017, relates what happened next.

JOE KAMIYA:

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor I was 16 years old. I remember thinking that the war would have some direct influence on my life because I was Japanese-American, but I didn’t know exactly what would happen. In February 1942 came Executive Order 9066, and then it was announced in the spring of 1942 that a military evacuation of people of Japanese descent run by Gen. DeWitt was going to take place. I didn’t like it, of course, partly because it meant that all contact with my friends whose parents came from Europe would be cut off. And most of my friends at the time were Caucasian.

The day we were evacuated we had to get up early in the morning. We got to bring one suitcase. We gathered together at the Cortez Church and boarded a bus that drove us some 20 miles to the Merced County fairgrounds, where the military had hastily erected these barrack-like structures where maybe 5 or 6 families per barracks were housed. It was called the Merced Assembly Center. There were a total of about 5,000 individuals imprisoned there, incarcerated, whatever you want to call it. It was a temporary camp to hold us before we were shipped to Camp Amache.

When we got there, we were registered and checked in the Merced County Display space. I remember it because that’s where I had displayed my chickens the year before. It was a Future Farmers of America project in high school, and my chickens won some blue ribbon prizes. Now I was in the same place, but I was a prisoner. [laughs] Fortunately some of my high school friends’ parents brought their kids to visit me. Robert Riley and Robert Madsen. Both of their parents were very sympathetic to us, and wanted to show us that they were not hostile to us, that it was the government that was.

I didn’t have much of a chance to talk to my friends. It all happened rather rapidly. We got the notice to be packed up and ready to go with only about one week notice.

I was sad about having to leave and go to the camps. But as soon as I got to Merced, and got registered I felt OK. I fairly quickly adapted to the circumstances. For one thing, I no longer had to work in the fields. At home, I got up in the morning, had breakfast and then went out to work. Same thing when I came home from school. I’d go out in the fields and pull weeds or pick strawberries or do whatever was necessary to keep our farm going. At the camp, I could play baseball with my buddies or do anything else the rest of the day, and come back for lunch and have dinner. I did much more playing around than at home. So it wasn’t a bad life at all for a 16-year-old. The older people really took a beating, but as a kid it was all right.

We were just in Merced for a few months while they were constructing Granada [Amache]. We took a very long, tortuous train ride, all the way down to Barstow, way below Bakersfield, and then through Arizona and New Mexico, across the Rockies and then back down to southeastern Colorado where Amache was. As I recall, the windows were papered over. I guess it was a security measure. There were armed guards on each train car.

Finally we got there. I guess we were carried by bus from the Granada train station two miles to Camp Amache. There were some people, internees who had arrived earlier, who greeted us—no big ceremony, they were just there to accompany us to our barracks.

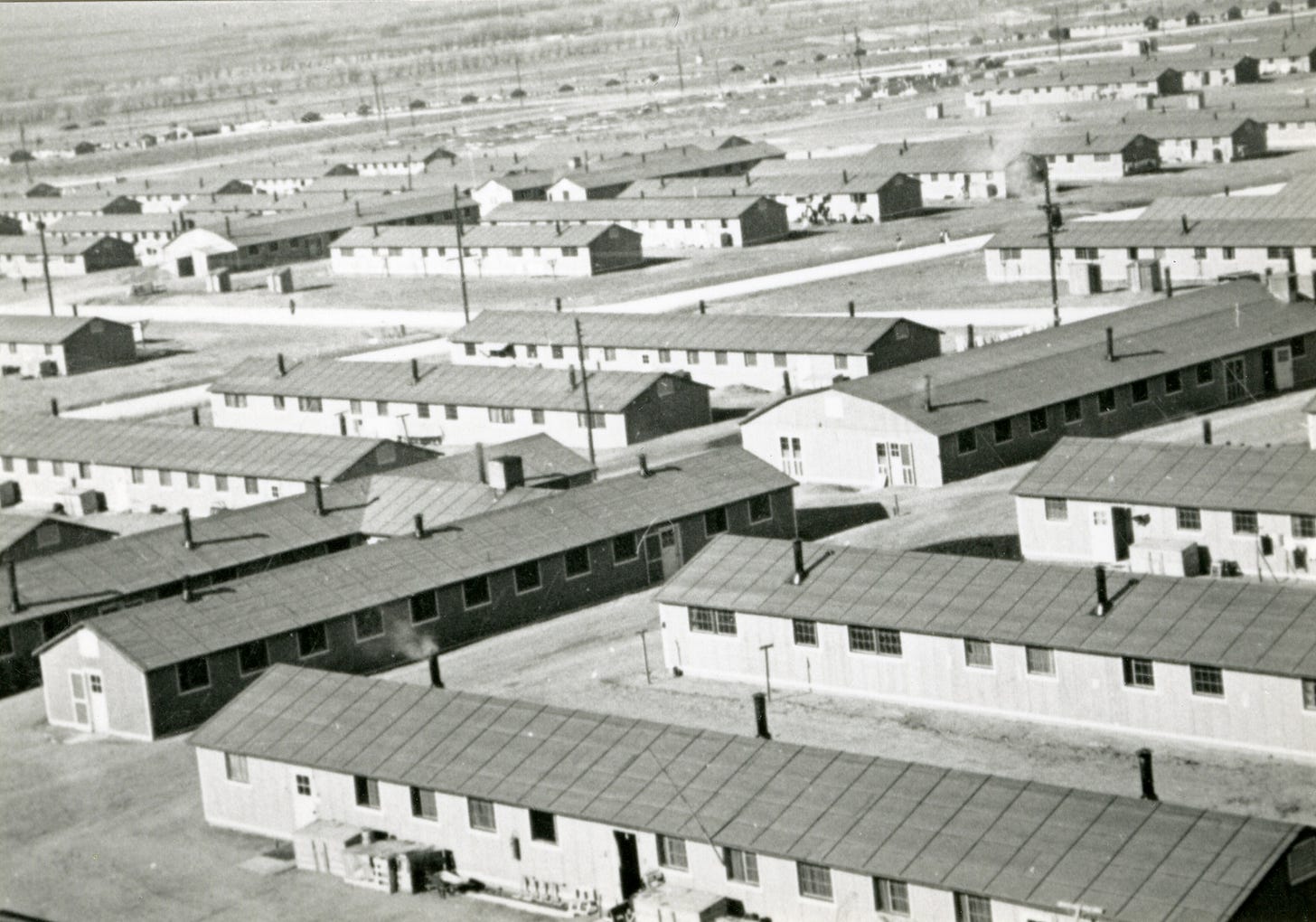

Camp Amache during WWII.

We settled down into Ward 6A. Building A in Ward 6. There was barbed wire on the perimeter of the camp, guard towers, and guards with rifles posted. But they stayed only maybe a few months. I think they discovered maybe that there was no real danger of us escaping. We were so law-abiding. We were taught that there was nothing holier than abiding by the law. There were only maybe 2 or 3 people who got jailed for resisting being put in the camps. I don’t know why we didn’t try to resist, but it would have been impossible in Cortez. Virtually every house in that neighborhood was Japanese. There was no juvenile delinquency by the way, no teenagers who were trouble. It’s because the Japanese are authoritarian and submissive. They’ve been that way in Japan for centuries. We carried on the same way here. You obeyed the law, no questions asked about it.

We did have quite a few “no-no” boys at the camp. [In 1943, U.S. authorities began requiring all adult males to answer a questionnaire intended to determine their loyalty. The first question asked if they were willing to serve in the armed forces of the U.S. The second asked if they would be willing to swear allegiance to the U.S. and forswear allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. For various reasons, including anger at being asked to swear allegiance to or serve in the army of a country that had imprisoned them without cause, some internees answered “no” to both questions. These so-called “no-no boys” were shipped to a special internment camp for “disloyals” in Tule Lake, California.] But that was not so much about going into the camps as about being drafted into the army. There was a much greater resistance to that.

It’s interesting to reflect on the fact that I felt I should volunteer my services to the U.S. Army. It’s a goddamn good thing that I was rejected because of a heart murmur, because I might well have been killed in Italy. At those bloody battles at Anzio and other places. I knew 2 or 3 people who were killed in Italy or France. They were in the 110th and the 442nd. Unless they were in Military Intelligence, like my brothers, the Nisei went into those units. [The 442nd Infantry Regiment, which was composed almost entirely of Nisei, is the most decorated unit in U.S. military history.]

Color guard of the 442nd Infantry Regiment stands at attention while their citations for bravery are read, near Bruyeres, France, Nov. 12, 1944.

Life at Amache was pretty tolerable. It was routine. They opened the high school right away. School normally opens in the fall and we arrived in the spring, so they had time to set up and recruit many of the Japanese guys who had already had experience teaching or were willing to work as teachers. They got paid all of $19 a month for full time teaching. And they were very similar to most of the high school teachers I had experienced, except one: Kathy Odum.

She was probably 30, a local girl from Colorado. She was very conscientious, her parents were very solid Christian, I’m sure conservative but loving parents. She was a loving person. She was especially sympathetic to the cause of the Japanese-American kids. She recognized us as individuals and encouraged us to talk about our lives. She had chosen to live on the camp, not in Granada, and she encouraged us to come down and visit at her place, a small apartment which she shared with another white teacher. We may even have had dinner there.

Kathy Odum had a big impact on my life, and a lot of the other Japanese kids in the camp as well. We kept in touch with each other over the years. We were pals. I liked her and she liked me. She took a special trip out here to San Francisco to visit me in my house in Corte Madera, as well as several other people who had been in the camps. She came at least twice. Her son Jack drove her out. She would write handwritten Christmas letters to her former students.

She was an amazing woman. She received a special award for Colorado women. I have the same kind of feelings for her that I do for my high agriculture teacher, Eldon Callister. [See previous story.] The outstanding characteristic they shared was that they loved us. They wanted to help us as much as they could, with whatever they were trained to do. For me, the message that came through was “Hey, here are some real people that are on my side.” I think they felt that it would be important not to let too many Japanese kids get bitter and completely anti-American.

Although I don’t know of anybody who became anti-American as a result of being in the camps. They could be critical of specific actions taken by the U.S., of course, but not totally anti-American in general. It really was remarkable. But it also points to a certain kind of cultural weakness, in my view, that Japanese were all too submissive to authority in Japan, where of course my parents and other Nisei’s parents came from. It was good in the sense they they were always very hospitable to strangers and others, but they also had very authoritarian, strict rules of behavior that everyone had to follow.

My days in high school were rewarding. Somehow or other, maybe because I didn’t hesitate to speak up in class, or at meetings of groups, I was elected the president of the senior class. That tells me that apparently I was not just a creeping-around, hiding-in-the-corner person. It was a good-sized high school. There were a couple of hundred students in the senior class, about 800 students total.

I didn’t have to work in the camp. If I wanted to work to make money, my friends and I would work in the sugar beet fields. We used long bladed knives with a hook on the end. You stooped over the sugar beet, which could weigh as much as 8-10 pounds, and top it off and throw the sugar beet into a pile. That was a backbreaker. I could sure feel the pain by the time I got through doing that. We got paid maybe a couple bucks an hour.

Life in the camp was harder for my mom, I think. It’s harder when you’re older to get ripped out of your home. And there was no privacy in the bathrooms, which was hard for the Issei women. She thought the internment was unjust, but she accepted her plight and took a leadership role in forming an association of Japanese women in the camp. And she was one of the elected officers of the camp. She wanted to help out the Japanese in the camp. More so than most Japanese mothers. And of course she was still not allowed to be a U.S. citizen until 1952, couldn’t own land or marry a Caucasian person.

After I graduated from high school in Amache, in June 1943, it was time for me to think about college. I would have liked to have gone straight to Berkeley, but at the time the military rules were that I could not as a Japanese person be in the states of California, Oregon or Washington. So I chose to apply to Colorado A&M college, Colorado Agriculture and Mechanic Arts College. It was a worthwhile experience, because there I was one of only a few students in most classes. The most numerous class had maybe 20 students. This was in January 1944, during the war, so most of the people were in the army or whatever. I went there for 3 full semesters. It was there that I learned that I loved the subject of physics. I remember the professor taught a class of three of us. This was a predominantly white college; possibly I was the only Japanese-American attending at that time.

There was no bigotry directed at me at all that I can remember. Not a single person ever said anything, except one guy. I was once on a lumber pile earning my living at a lumber yard, and this guy was an inspector, a state or federal inspector. He would turn each plank over upside down, and then indicate to me that I could hand it down to the next guy below. He asked me if I was Japanese, and I said, yes, I was. “Oh, well you’re a Jap,” he said. I felt the blood pressure surge of resentment, and for a moment I thought, “Wouldn’t it be nice if I just tossed this guy off the top of the lumber pile.” It was a good ten feet. [laughs] But then I decided I could get in real trouble doing that, so I held in my resentment. I was very seldom called a Jap by anyone. It was an ugly term, like being called a nigger. Its use started long before World War II, of course. That was one of the fairly rare instances of overt racial bias that I confronted.

When I attended Colorado A&M, I was not required to return to the camp at night. I was given an indefinite leave, and they never held me to any particular date to return. But I did go back to the camp to visit my mother, who was the only one in my family who was still there. My two brothers were in the military by that time. No other family members were in the camp. But much of the entire Cortez Japanese colony was still there and many of my friends were still there, Kyoshi Yamamoto and many others.

I was accepted to U.C. Berkeley, and in January 1945, I took the train alone from Colorado to Berkeley. I was the first Nisei to attend U.C. Berkeley after the war. When I got off the train, these guys from Stiles Hall were there to meet me. Stiles Hall was a unique Berkeley institution, originally a YMCA, whose main cause was civil liberties and civic activism. Harry Kingman and other folks met me at the train station. I felt very good about that. It was a wonderful greeting. Within a couple of years I became a part-time member of the staff at Stiles Hall.

When I first came to Berkeley I stayed with my mother, who had moved to Berkeley, maybe a year or two before she moved back to the farm. She lived in the Elmwood district, in a cottage on an English professor’s lot. He apparently had some sympathy for Japanese people who had just come back from the camps, and he helped my mother get housing. She stayed in his cottage and essentially served as his domestic servant, doing his house cleaning and so on.

When I entered Berkeley in January it was mid-term. The war was still going on; it wouldn’t end in the Pacific for eight more months. I was working part time to support myself at the Daily Californian, the student newspaper, as a flyboy. My job was to get the papers hot off the presses and stack them up and get them ready for delivery. That was around the time of the surrender. By then I had almost a year under my belt at U.C. I remember the day of surrender well. There was a great celebration. No one made any reference to the fact that I was of Japanese descent. I was a worker at the Daily Cal, I was good friends with the editor, we were all celebrating together, and it didn’t matter that I was Japanese. That was a great day.

After my mother went back to the farm, I moved to Bowles Hall, a U.C. men’s residence, very posh, up above the football field. This was a special place where you got in because your father had gone there or had given a lot of money. I think they took me because they were trying to do the right thing by admitting a Japanese-American.

Almost every weekend I’d drive back to Ballico and run the farm, then drive back to Berkeley. I drove the Model A Ford pickup from the farm.

Our farm, and all the farms in the Cortez Colony, made it through the war and we and all the other owners got their land back. We were fortunate because we were already organized as a community. We were part of the Cortez Japanese-American farming community, and we had formed a producers’ cooperative called the Cortez Growers Association. All the things we raised we took to one central place, and the manager took care of its distribution. We had a semitruck and trailer which loaded up all the eggplants, squash, strawberries, and grapes which we Japanese farmers raised in Cortez, and delivered them to retail and wholesale outlets in San Francisco, Oakland, wherever they sold it. The coop was a very non-competitive cooperative. We were Japanese exclusively at the beginning, then a few white folks came in along the way. The coop started in the 1920s, I think, not long after the foundation of the Cortez Colony itself. It was formed along the Santa Fe railroad tracks, and we had a stop there so we could load our stuff right next to the tracks. That helped us thrive because we could get that stuff sent to market every day.

When we had to leave for the camps, we managed to hire a trusted white manager to take care of the farms, by leasing the farms to tenants. It was done under supervision, it wasn’t each farmer working for himself. Every farmer hired this guy to do it, and he did a good job of it. His name was Gus Momberg. He was known to be a good guy and he was a good manager. I think he was paid a salary that was much higher than we paid our own Japanese managers, but that was probably par for the course. And he brought in good, reliable tenants. He arranged for individual farmers to come and live in the houses we lived in and run the patch of ground that we had been farming.

So we had a family living on our farm. We were glad that at least we were receiving a proper accounting of how much was made and so on. We had some grapes, and we had an almond orchard that had just come into production. The trees were at most 4 or 5 years old, but by that time almonds begin to bear enough that they begin to pay off the initial cultivation. I remember planting them 30 feet apart. We had stakes to plant out the places. My brothers did the planting, and I just followed along, I guess. I think the tenants who lived and worked on our farm sold the crops through the same coop. And when the war came to an end, it was pretty straightforward. We came back, the tenants left, Momberg left and a Japanese manager took over. It was very smooth. No one in the Cortez colony no one lost their land. I know that that was not always the case.

I never heard of any predatory people who wanted to snatch up our land. Although there were one or two bigots who might have fired shotgun blasts at some of the houses. That did happen. Fortunately it didn’t happen to our house. And it happened only once or twice, it was not a regular thing. I suspect that the Turlock and Merced county police were probably alert to the possibility of that, to make sure that a lot of vigilantes were not standing there preventing us from taking back our farms.

It actually didn’t feel that strange to come back from the camps where I had been for several years and go to this prestigious university. Yes, it was a big change but it was pretty much a matter of course. I’d been expecting to do it ever since I was in high school, I guess.

My mom was healthy and took an active part in the Cortez community. She was the president of the Issei’s church membership. They had a Japanese language speaking minister and he spoke in the mornings, first giving sermons in Japanese and later in English. He was kind of a fundamentalist. My mother was always devout, as far as I can remember. She went to my father’s gravesite every other week and prayed for him by his gravesite. He was also Christian, but his family had been Buddhist. I think he became Christian at the insistence of my mother.

My mother did some of the farm work herself. She picked strawberries and eggplants and packed stuff. She did what she was physically able to do and what she was not able to do, my older brothers did after they left the military. When I came back on weekends, I would irrigate strawberries and eggplants, prune the almond trees in the fall, and haul the brush to a place where I burned it. We had help to do most of the picking. The pickers were Filipino. That was common. We also had one Okie, Ernie Beard, who grew up in Oklahoma. He came out in the Dust Bowl, lived in Delhi, and drove a Model A Ford every day to come work on our farm. He was a very trusted and liked person and he was very dedicated to supporting us.

All in all, after the end of the war there was a pretty good harmony among the townspeople, white and Japanese. We just picked things up where they were before.

Meanwhile, I was still occasionally pondering the meaning of life, but it was nowhere near the slightly pathological form that it took earlier. It became more of an academic interest. I was no longer personally and spiritually tangled up with it. I was studying it more like one would study physics. And that was a salvation for me, because I found that being buried in one’s introspection was a pretty rough way to solve problems. [chuckles].

I realized within the first year at Berkeley that I wanted to major in psychology. It came naturally as a better approach to my introspective meanderings. The study of psychology was the study of the mind, after all. And so even though it was purely objectivistic, it seemed to hold the key to the most important questions that could be asked about human beings. Anyway, I liked the textbooks, I liked the lectures, so I stayed with it. I graduated with my bachelors in 1948, and I got my PhD in 1953, I think.

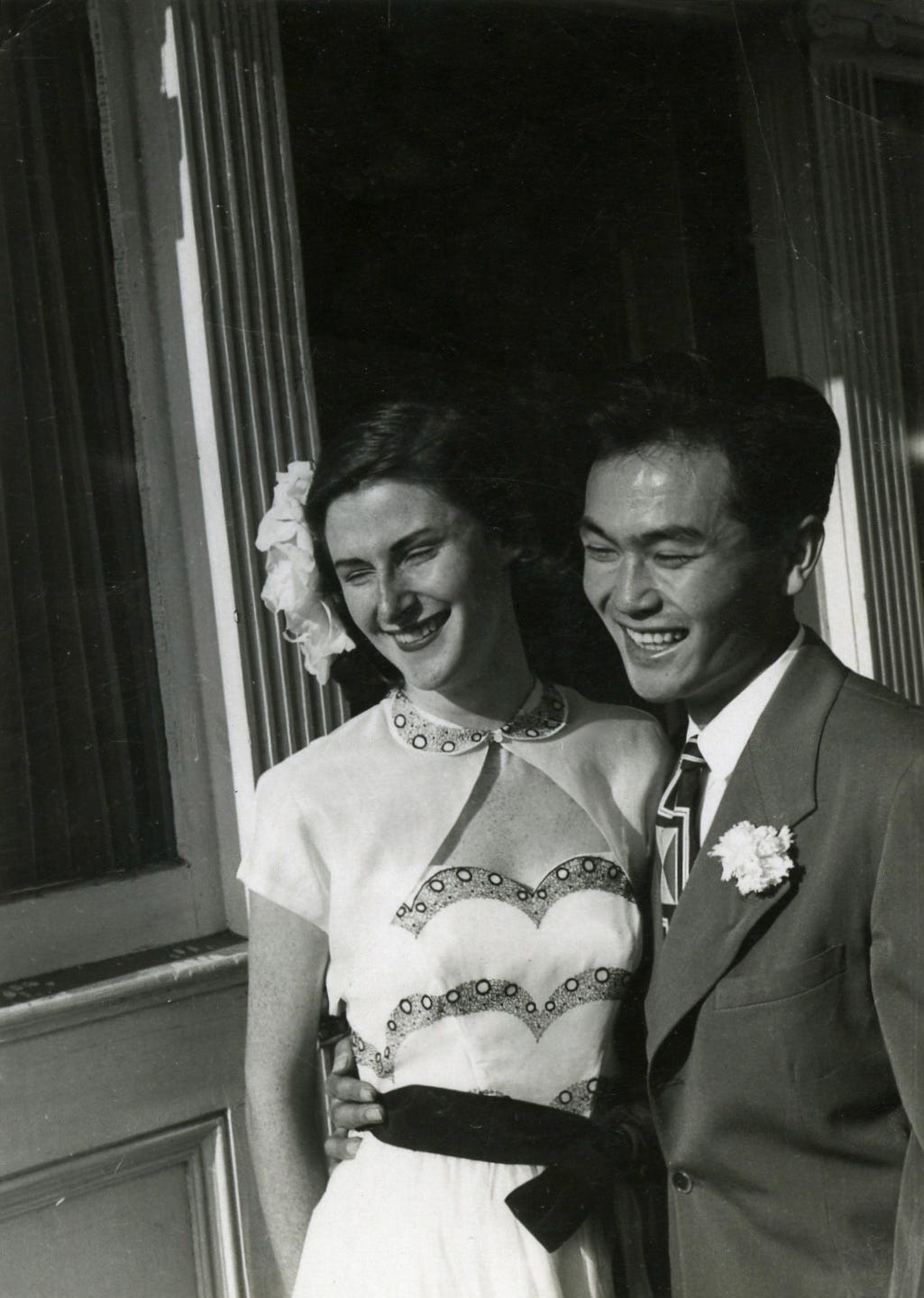

It was while I was staying at Bowles Hall in my senior year that I met Bob Alford. We were roommates together. We hit it off right away. Immediately. And he was very sympathetic to me, and helped me get adapted to Bowles, and told me that things about it that I would need to know. And shortly after that I met his sister, Dorothy.

Dorothy Walker was my mother. Joe and Dorothy were married in 1950 and had three children. They were divorced in 1962 but became friends again late in life. Joe Kamiya went on to become one of the seminal figures in the field of biofeedback.