The mystery in the Mediterranean

Jewel box, site of two epic sieges, at once monumental and toylike, Malta is unlike anywhere else on earth.

I haven’t posted anything here for a couple of months because I was on a 3-week trip to Malta and Sicily. I got back a month ago and have been trying to write down some of my eight million impressions before they vanish into everyday oblivion. It was a glorious trip, filled with more neural overload than even the most hardcore sensation junkie could desire, a cornucopia of erupting volcanos, bombed-out buildings rotting away since 1943, careening ape cars, magic tiny beaches at the bottom of secret steps, Roman mosaics depicting a world so vivid, erotic, amoral and full of unruly life you wonder how the hell we ended up with a weird monotheistic cult whose symbol is a crucified God, mighty forts on toy-like Mediterranean harbors where Christian knights and their Muslim foes clashed in the most brutal siege of all time, seas of pellucid turquoise, raucous urban celebrations marked by extremely loud and terrible music, intermittent explosions, and barbeques smoking like the fires of Hades, Greek temples so timeless they would have inspired Keats to pen another immortal ode to immortality, the best food in the world, astonishingly beautiful and warm-hearted people, three WWII biplanes that soared into legend, bizarrely lascivious groups of statues, and a host of ancient, wondrous cities and towns, each possessing its own intricate, convoluted, magnificent arrangements of buildings and shadows and streets, streets, always streets. Streets that are poems in stone, random, epic byways created by vanished demigods whose only task was to make human trails through cities divine. When I close my eyes and think about this just-concluded adventure, it’s those streets that first fill my mind. And not just because venturing down them, whether behind the wheel of a car or on foot, was a constant near-death experience.

The trip started in London, where I joined up with my girlfriend Elizabeth for an afternoon and night before we flew to Malta and Sicily. Our day in Bertie Wooster’s beloved Metrop started out with rain, of course, and just as predictably ended up with shafts of golden sunlight falling on Shaftesbury Avenue. Ah, what joy to be dazed and confused once again in London, that alchemical combination of monumentality, reserve, and tremendous excitement. We wandered aimlessly around Soho and Piccadilly, digging the crowds on Regent Street, marveling at London’s unparalleled cultural and ethnic and racial diversity, cracking up at a huge sign on a Chinatown club blaring “Award Winning Gay Bar” (would anyone go to a gay bar because it was “award winning”? And just what award would that be?) and popping into a pub for a pint of what Dylan Thomas a bit too affectionately called “flat, warm, thin, Welsh, bitter beer,” an accurate enough description except for the Welsh part. I was slightly embarrassed because I kept getting lost trying to find Trafalgar Square, even though I lived for a year in Birmingham and have visited London many times. Finally we made it to towering Lord Nelson and his guardian lions. We wanted to go to Green Park and St. James Park, those elegant twin marvels that are the verdant bull’s eye of London, but were jet lagged enough not to care that we didn’t make it. We looked down The Mall to distant Buckingham Palace, satisfied with the little flakes of the great city that had fallen to us. Later we ate the best Indian meal I’ve ever had at some almost-empty joint we stumbled into at random. In a surreal ending to the evening, we took the tube to Gatwick and stayed in a hotel that was actually located inside the airport. The window of our tiny, hermetically-sealed room looked down on a runway, and when you went sleepily downstairs you found yourself in the bustling middle of departures. It was pragmatic to the point of humiliation, but an excellent choice if you had a 6:30 a.m. flight to Malta.

We landed at the airport outside Valletta, the capital of Malta, on the morning of April 17. A tremendous, gale-force wind was blowing as we waited for the bus to take us into town. Palm trees were bent almost in half, and dust was flying wildly over the dreary yellow-ish modern buildings around the airport. The place seemed to have a vaguely North African cast, or maybe that was just my imagination, stimulated by the fact that we were on a tiny island south of Sicily and at a lower latitude than Tunis, in a part of the Mediterranean whose page on my mental map was smudged to the point of illegibility. The first bus simply drove past us, confirming the truth of an e-mail sent by our hotel warning us that public transportation here was extremely unreliable. We conferred with a gaggle of fellow new arrivals; no one knew anything. After another half hour or so another bus finally appeared. The surly, bullet-headed bus driver—the only surly person we were to meet in Malta—said his credit card machine was broken and demanded payment in cash. We didn’t have any cash, but we didn’t want to subject ourselves any longer to the whims of the Godot Bus Company, so we just walked past him and sat down. After a longish bus ride through dreary districts we got off and promptly got lost looking for our hotel, which was located somewhere in a pocket-sized residential quarter in a ramshackle neighborhood called Floriana. We found ourselves next to a strange huge paved area, past a massive Baroque church, that was filled with dozens of what looked like oversized stone manhole covers, laid out at regular intervals. These turned out to be granaries, built in the 17th and 18th centuries, which came in handy when the Fascists and Nazis were pummeling Malta from the air. Eventually we found our hotel, which was a beautifully renovated old building that stood out in our charming and slightly bedraggled quarter.

As we walked up towards the center of Valletta, I was already experiencing that edgy but open-minded sense of anticipation you get when you’re in a new country, and that feeling of falling into mystery deepened as we walked past a little park and a stunning view of Valletta’s Grand Harbour came into view to the right. I’d never seen a view quite like this. It was one of the greatest natural harbors in the world, but it was oddly miniature-looking, with finger-like inlets that made it feel a little like a combination of Sydney and Point Reyes. Equally disorienting was its complicated shape, like a really easy jigsaw puzzle piece. This was just one side of the Grand Harbour: it extended on both sides of the peninsula on which Valletta stood. I was still disoriented and thought I was looking at the other side of the harbor, whose name, in the strange, tongue-twisting language spoken here, was Marsamxett.

A few minutes later we walked into one of the most unique cities I’d ever seen.

I was almost completely ignorant of Malta. It was a bonus throw-in to Sicily: we’d only come because a cheap British Airlines flight landed here, after which we were going to catch the short flight to Catania. The half-dozen playing cards in my Maltese deck were a paltry collection of jokers. I knew Malta was a tiny island nation, and that it was in the European Union—at 122 square miles, the EU’s smallest country. I knew that a disproportionate number of luxury yachts use Valletta as their home port. I knew that Maltese was a Semitic language, a variant of Arabic (the Maltese, who are devoutly Christian, call God “Alla”), and the only Semitic language written in a Latin script. I was vaguely aware that Malta had a reputation for high-level corruption and that a leading Maltese investigative reporter had been assassinated in 2017. I knew that Malta had been a longtime colony of the UK and, thanks to its strategic location south of Sicily, been a crucial British base in World War II and endured intense bombing by the Italians and the Germans. I knew Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon. And I knew that Thomas Pynchon had set some of his novel V in Valletta.

But the only subject related to Malta I really knew anything about was the Great Siege of Malta.

I only learned about that siege out of weird happenstance. Last October, while I was walking on a hill atop the troglodyte village of Troo, France, I came upon one of those street-library book boxes that have happily popped up around the world. I needed something to read on the plane, so I looked inside the box and found a little paperback called The Great Siege of Malta. The subject was right down my alley: extremely violent, historically momentous, and obscure. I had no idea that six months later I find myself standing on the scene of that world-historical battle.

Ernle Bradford’s 1961 book recounted the epic 1565 struggle between the Ottoman Empire under Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and the Knights of St. John, also known as the Knights Hospitaller, a devout and militarily formidable order that originated in the Crusades and had moved to Malta after the Ottomans forced them out of their stronghold on Rhodes. (In return for occupying Malta, the Knights were required to give Emperor Charles V an annual tribute of one Maltese falcon— a historical footnote immortalized by Dashiell Hammett.) At stake was control of the Mediterranean. After a savage four-month siege that featured such unpleasant tactics as firing severed heads over the walls, floating crucified enemy corpses on rafts across the harbor, and slaughtering prisoners to the last man, the few hundred Knights, their five or six thousand Maltese allies and their indomitable 70-year-old leader, Grand Master Jean Parisot de Valette, somehow prevailed against 40,000 Ottoman troops. It was a turning point in the early modern clash of civilizations whose final encounter, the great sea battle at Lepanto where Cervantes was wounded, took place six years later. For centuries, it was one of the most famous battles in world history: Voltaire once said, “Nothing is better known than the siege of Malta.” Today it is almost entirely forgotten. The city of Valletta was built by the Knights after the siege and is named after de Valette.

My knowledge of this 459-year-old siege, and the rest of the few dubious scraps of knowledge I possessed, left Valletta a complete tabula rasa for me. I could make up the weirdest city in the world around what I knew about it. And Valletta turned out to be even more unclassifiable than I could have imagined.

The first thing that strikes you about Valletta is how narrow it is. It stands on a little humpbacked spit of land, the Sciberras peninsula, that’s only eight blocks wide and is surrounded on three sides by water, so that views of the sea pop up at the end of every street. This gives Valletta something of the quality of Cadiz, Spain, another enchanting small city enclosed by the sea. But the historic heart of Valletta is much smaller than Cadiz, and its tiny dimensions, combined with the disproportionate number of monumental structures it contains, gives it an out-of-scale quality that’s both charming and disorienting: It feels simultaneously epic and toylike. The main square that greets you as you enter, consisting of a new City Gate, a new Parliament building and a new theater built within the bombed-out ruins of the old Opera House, the entire ensemble designed by Renzo Piano, heightens this sense. The grand City Gate has a larger-than-life, slightly disturbing quality, faintly suggestive of the Great Temple of Luxor, that is the perfect antechamber to the main square, with its peculiarly heterogeneous atmosphere of mingled grandeur, tourism, and destruction. Once you walk into town, you find yourself in the midst of buildings impossible to place—sand-colored Baroque houses, whose pop-out enclosed Maltese balconies are weirdly reminiscent of Ottoman architecture.

But it’s Valletta’s location, on its unique, convoluted, two-sided harbor, that truly sets it apart. In particular, the view across the eastern side of the harbor to the three ancient yellowish towns known as the Three Cities is unlike any other view I’ve ever seen. The Three Cities, headed by great waterfront forts where most of the fighting in the Great Siege took place, are so dreamlike and atmospheric they seem to have been lifted from the background of an early Renaissance painting. But despite their fantastic, otherworldly quality, they’re disconcertingly close: the boat ride across the harbor only takes a few minutes. It’s as if time has been translated into space, and in a quarter of an hour you can stroll into the Crusades.

Across the Grand Harbour to the Three Cities, seen from Upper Barrakka Gardens in Valletta.

And speaking of time, Malta’s history is head-spinning. Like Sicily, this island was conquered or ruled by everybody who sailed through the central Mediterranean—Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Romans, Muslims, Normans, Aragonese, Charles V’s Holy Roman Empire, the Knights of Malta, the French under Napoleon, the British. That’s entirely too much history for a place this small.

All these elements create an almost extraterrestrial sense, a feeling that you’ve landed on another planet, or a stage set for a dream city set in an alternate universe. It’s like you’re wandering through a city made up of architectural follies, an entire place made up of dozens of fantastical iterations of San Francisco’s Palace of Fine Arts.

Valletta’s Renzo Piano-designed main square, with the Parliament House on the right and the new open-air performance space in the bombed-out Opera House behind it.

We walked to the end of the peninsula, not far from massive Fort St. Elmo, which heroically fought off the first wave of Suleiman’s warriors until it fell and its defenders were slaughtered. We had lunch at a venerable restaurant called Nenu, which specializes in the traditional Maltese flatbread called ftajjar. There were quite a few people on the streets, mostly European tourists, but it wasn’t overrun. Valletta was obviously a major tourist town, and no doubt a madhouse in high season, but the vulgar signage and tourist-trap quotient was pretty low. Several of the steep cross streets that run down from the central spine of the little peninsula in both directions were filled with restaurants and bars, and there were lots of people sitting on tables placed precariously on the steps, eating and drinking Aperol Spritzes in fishbowl glasses— a charming, quintessentially Mediterranean scene.

Restaurants on one of Valletta’s cross-streets at night.

We wandered around town, meandering through a gorgeous little park called Upper Barrakka Gardens, which overlooked the harbor and was connected to it by a massive, industrial-looking lift. We ate an al fresco dinner—a “Jazz Platter” piled high with different cheeses and meats— at a restaurant called Luciano’s, on a large landing next to an elegant stone staircase descending to a street below. The surrounding streets had a faintly Parisian atmosphere, mixed with a bit of Spain and a touch of North Africa. A very hip jazz playlist was wafting out of the restaurant. We walked back through the main square, where those insane winds were still blowing (the grid of narrow streets mercifully seemed to block them when you were in the heart of Valletta) and back through deserted streets to our hotel. “We’re in Malta!” we said to each other when we got back to our room. We still didn’t know what that meant. We wanted to find out, but we also didn’t. Strangeness is golden, and it’s getting harder and harder to find.

The outdoor seating at Luciano’s restaurant, on an elegant landing above a grand staircase.

We spent three days and nights in Valletta. We spent an afternoon in Fort St. Elmo and its National War Museum, which did a decent job on the Great Siege of 1565 but a first-rate one on the second great siege the island endured, during World War II, when as a crucial British base in the Mediterranean it was bombed more heavily than anywhere else on earth. I was and am deeply interested in World War II—my first book, Shadow Knights: The Secret War Against Hitler, was about the exploits of the men and women who volunteered to serve in Britain’s top-secret Special Operations Executive, which aided resistance movements in occupied countries—but I knew next to nothing about Malta’s role in the war. As I explored the World War II rooms, one exhibition caught my eye: the fuselage of an old Glocester Gladiator, a British biplane. The accompanying text said that this outdated little plane and its two sister aircraft, nicknamed “Faith,” “Hope” and “Charity,” were the symbols of Malta’s heroic, years-long resistance to the brutal Axis siege. The room also displayed two paintings of the three planes. One of them depicted a ground crew changing the propeller on one of the planes. The other showed the three little planes flying in formation above the church we had walked past when we first arrived, St. Publius. The church had been bombed, and a heap of rubble was piled in front of it, on the edge of the field containing those odd granaries. Behind the planes, the artist had painted a ghostly angel, its arms extended out across the sky as if protecting the planes. The painting was totally corny and over the top, but it stuck in my mind, and when I got home, I started looking into the story of those three biplanes. My research took me pretty deep down a Malta-in-World War II rabbit hole. I tell the amazing story of “Faith,” “Hope” and “Charity” in this accompanying piece.

Looking across Marsamxett Harbour from near Ft. St. Elmo.

The connection between Malta and Britain is deep and intriguing. Malta was a British colony for 150 years, from 1814 to 1964. When Paul Theroux visited there for his 1995 book The Pillars of Hercules, he found the British influence still very evident. “Malta had the culture of South London in a landscape like Lebanon—news agents selling The Express and The Daily Telegraph, video rental agencies, pinball parlors, pizza joints, and a large Marks and Spencer. All those, as well as fortresses and churches and many shops that sold brass door-knockers. But chip-shops and cannons predominated,” he wrote.

Theroux found Valletta barren, boring, broke, priest-ridden, and so forgettable that he put it on a really bad list he created, “the most irritating Mediterranean places to live and be creative.” He was kinder to the Maltese people, of whom he wrote, “The Maltese seemed approachable, friendly, rather lost, a bit homely, dreamy, decent and well-turned-out. The garrison atmosphere was much the same as I had found in Gibraltar. Even the Maltese who had never been in England had a sort of shy pride in their English connection and spoke the language well.

“The English had found these people, used them to service their fleet and dance for their soldiers, educated them, made them into barbers and brass-polishers, turned over to them London lower-middle-class culture and the sailor values of folk dances, fish-and-chips, BBC sitcoms and reverence for the Royal Family, and given them a medal. Every schoolboy—Maltese as well as British—knew that Malta had been awarded the George Cross for bravery in the last war.

“But the British soldiers had left, the brothels and most of the bars were closed, business was awful here too, and at a time when most British war heroes were auctioning off their medals at Sotheby’s—a Victoria Cross was worth about $200,000—Malta’s medal was hardly valuable enough to keep the economy going. The neighbor island of Gozo was the haunt of retirees living off small pensions. The only hope was in Malta’s joining the European Community, to make the islands viable.”

Looking from a cross street to the Three Cities.

Thankfully, Valletta no longer bears much resemblance to the tedious place Theroux described just 30 years ago. Whether it was EU membership (Malta joined in 2004) or for other reasons, the city feels prosperous and lively, and the fusty-musty, overcooked-veg British legacy Theroux described has largely faded away. There are things that still evoke the Crown Colony days. Strait Street, which runs the length of the town, was once a raunchy fleshpot filled with bars and brothels catering to British troops; it’s still a jumping nightlife street, but the sinful days when it was known as “The Gut” are long gone. Another faint echo of British rule is found in the name of one of Valletta’s band clubs, the King’s Own Band Club, founded in 1874 and named after Edward VII. Band clubs are unique Maltese neighborhood institutions: they host bands that play at the four major religious feasts celebrated by the city’s churches each year, but also serve as cultural centers, restaurants, and places to drop in, have a drink, or play a game of pool. Valletta’s band clubs seem to cover the socio-economic spectrum. The King’s Own is an upscale club in the heart of Valletta with a beautifully refurbished dining room that serves spectacular, and reasonably priced, food. Another band club in our working-class neighborhood of Floriana, the Vilhena, was much funkier. It was located under an arcade next to a noisy, car-filled street, and was a local’s hangout. The night before we left, it was packed with by far the hippest crowd we saw in Malta, arty, intellectual, grad-student types listening to a jazz combo. Clearly, there were aspects of this place we had no idea of.

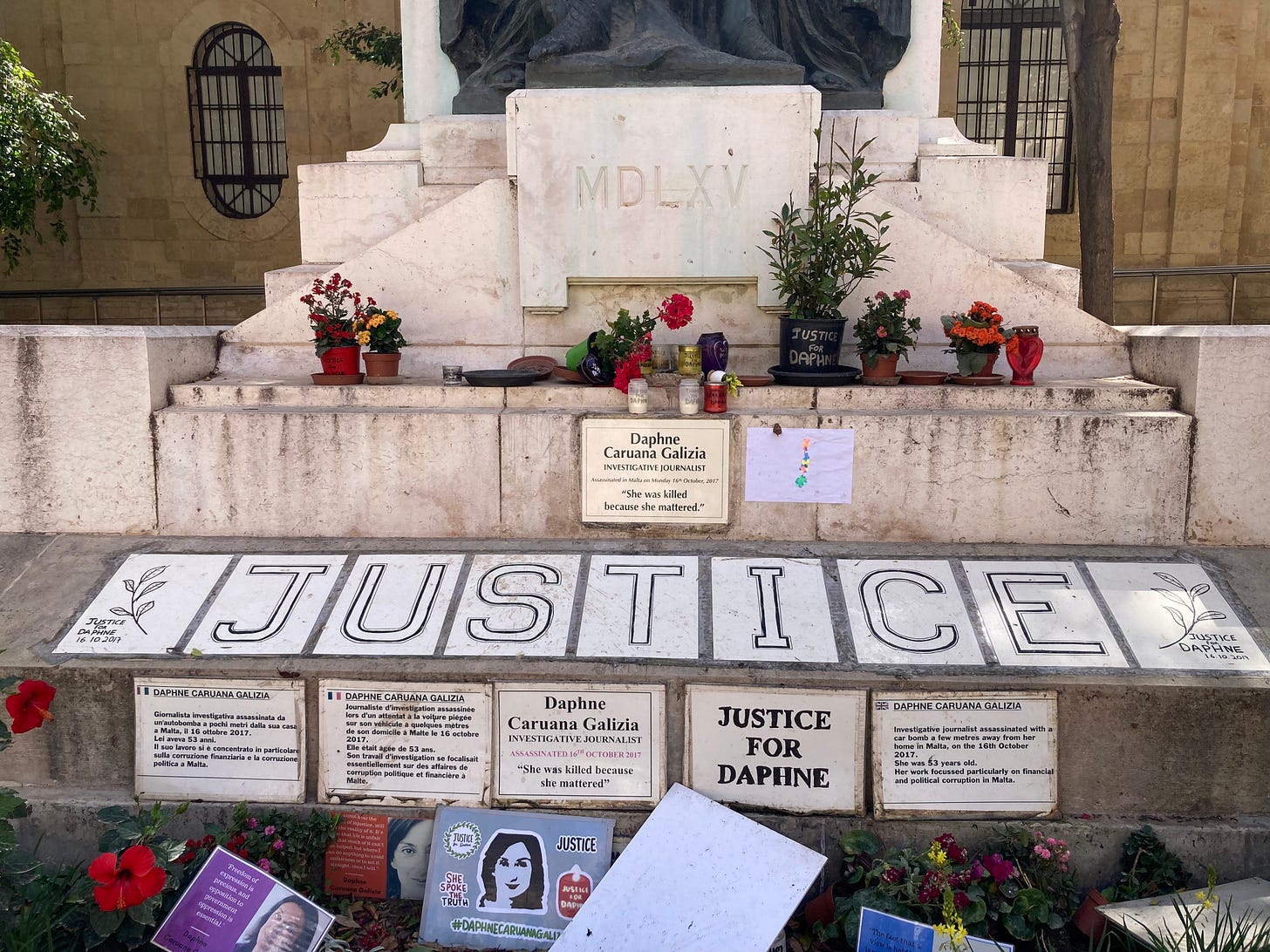

In fact, there were many of them, and not all ones the tourist guides like to linger on. Malta has a dark side, and you’re starkly reminded of it moments after you walk through the City Gate. As you walk down the city’s main street, Republic Street (in Maltese, Triq ir-Repubblika), you come upon The Great Siege Monument, a 1926 Neoclassic statuary group of three allegorical figures depicting Faith, Fortitude and Civilization. The base of this monument is covered with flowers and messages, makeshift memorials to an investigative reporter named Daphne Caruana Galizia, who was assassinated by a car bomb in 2017. People began placing these memorials here immediately after she was murdered. Malta’s Justice Minister initially ordered them removed, kicking off a daily ritual in which protesters would erect the memorials and the police would remove them. In 2020 a Maltese court found that their removal violated the protesters’ freedom of speech. They are now a permanent fixture adorning Valletta’s most significant monument.

The memorial shrine to slain journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, at the foot of the Great Siege Monument.

Caruana Galizia was killed because she was investigating corruption and malfeasance at the highest levels of the Maltese government. In 2020, Malta’s prime minister, Joseph Muscat, resigned after his chief of staff and two other ministers were questioned as part of the police investigation. In 2021, a board of inquiry made up of former Maltese judges found that the Maltese state was responsible for the murder by creating an “atmosphere of impunity” that encouraged Caruana Galizia’s assassins to believe they would face minimal consequences.

All of this was disturbing. But as an outsider who hadn’t studied Malta’s current political, economic and social situation, I had no way of knowing the deeper story— how seriously the authorities were taking the case, how deeply embedded corruption is in the country, and a host of other questions. Was Malta like Sicily before the assassination of Falcone and Borsellino, plagued by the Mafia and the code of omerta, or after, when their heroic lives and deaths galvanized the Sicilian people into action? I didn’t know, or whether it was even fair to compare Malta’s corruption and crime problem to the Mafia. It was a big mystery in a place filled with less consequential ones.

The next day we visited Malta’s most famous church, St. John’s Co-Cathedral, a plain-looking pile from the outside that turned out to have one of the most over-the-top Baroque interiors of any church in the world, as opulent as the Gesu in Rome. It was built after the Great Siege of Malta by the victorious Knights of St. John. In Besieged: The World War II Ordeal of Malta 1940-1942, Charles Jellison offers historical context that explains not just the splendor of St. John’s, but why Valletta is such an overflowing jewel box.

“The defeat of the Turks ushered in the great age of the Knights of Malta, as they were now commonly called,” Jellison writes. “Showered with riches from grateful princes and churchmen of western Europe, they proceeded to spend lavishly on the beautification and overall improvement of their tiny domain, especially the Grand Harbour area, where the Order’s presence and activities had from the first been centered. In 1566, the year after the siege, the Knights began construction of a new city (called) Valletta… in what Disraeli would describe as ‘a city for gentlemen built by gentlemen’…As the years passed, the Grand Harbor area, and Valletta especially, took on a majestic elegance and grace scarcely matched anywhere else in the world. Magnificent churches, law courts, theaters, hospitals and auberges to house the various language groups of the Order were erected with little regard for expense and adorned with precious art treasures imported from various parts of Europe.”

Nowhere in Valletta are the riches showered upon the Knights of Malta more luxuriantly displayed than in St. John’s Co-Cathedral. (Its unusual name means that it has equal ecclesiastical status with St. Paul’s Cathedral in Mdina, the official seat of the Archbishop of Malta). The Cathedral’s most intriguing feature is its eight chapels, each dedicated to one of the eight langues, or “tongues,” of the Knights of St. John. These langues were one of the more fascinating groups in the history of Europe. They were devout, warlike posses composed of international knights, each posse drawn from one of eight different European geographic and ethno-linguistic areas: the Crown of Aragon, Auvergne, the Crown of Castile, the Kingdom of England, France, Holy Roman Empire, Italy and Provence. Before the Great Siege, Grand Master La Vallette sent out an appeal to the Knights of every langue, scattered across Europe, to hasten to the defense of Malta. This was a near-suicidal mission, and it reveals how deeply loyal the Knights were that 500 of them answered La Vallette’s call. Each of the chapels dedicated to a langue was different—some were mind-bogglingly rich in ornamentation, others more restrained. As an ensemble, they were a gloriously hyperbolic, bursting-at-the-seams celebration of a stark ethos of bloody piety.

The opulent Baroque interior of St. John’s Co-Cathedral.

Emerging from this almost psychotic explosion of holy bling, we walked around the town, eventually making our way down to the harbor across from the Three Cities. Near where the cruise ships berth, we found ourselves on a supposed attraction called the Valletta Waterfront. The Valletta Waterfront was pitched as a tourist attraction, but it was a dismal flop, a moribund, cheesy and artificial-feeling implant on a dreary, utilitarian stretch of the shoreline, with a few newish and uninspired restaurants catering to cruise passengers. It was a relief to go back uphill into town, where the forlorn and run-down stretches at least felt real.

On our third and final day in Malta we wanted to see at least one other part of the country than Valletta, so we took a ferry over to Birgu (now called Vittoriosa), the central and most important of the Three Cities. We wanted to ride in one of the small gondola-like boats called dghajjes tal-pass, which we’d watched ferrying passengers across the harbor the day before, but it was too windy for them to operate. The Grand Harbour is so narrow here that during the Great Siege, some fearless Maltese swimmers used to swim across it under Turkish fire. It only took a few minutes before the ferry approached Fort St. Angelo, the great fortress at the mouth of the Birgu harbor. But after the ferry entered the inlet between the city of Senglea on the right and Birgu on the left, it just kept going on, and on, and on. This small inlet, much of it filled with yacht berths, was much longer than the part of the Grand Harbour we’d just crossed—a disconcerting fact that somehow felt very much in character with Jigsaw Puzzle Piece Bay.

We got off the ferry and wandered around Birgu. It was much more low-key than Valletta, with few monuments, but its narrow streets and golden-colored buildings had a sleepy, hypnotic appeal. On one of those winding streets, Triq it-Tramuntana (North Street), we came upon an ancient-looking stone building with an unusual arched window decorated with palm motifs.

The ancient Siculo-Norman house restored by Charlie Bugeja in Birgu.

When we walked into its courtyard, we encountered an older man who was doing some work on the building. He was a soft-spoken and unassuming Maltese fellow who introduced himself as Charlie. Charlie told us that he had bought the building in 2000 and had been restoring it for years. He said it was from the 13th century, with an even older basement. It was probably the oldest building in Birgu, and one of the oldest in all of Malta. It was built in the “Siculo-Norman” style, which originated in Sicily when it was under Norman rule and blended Lombard, Islamic and Byzantine architectural styles. He said it had been a nobleman’s house. He took us down to the basement, proudly showing us how he had illuminated it with terra cotta pots. “This was a stable,” he said. “Back then, only wealthy people had horses.” He said a high-ranking Knight of St. John probably used it as a residence during the Great Siege. I imagined an Aragonese or English or Provencal knight staggering down Triq it-Tramuntana half a millennium ago, bleeding from half a dozen wounds, collapsing on a cot before returning to the battlements the next morning. Charlie’s ancient house was a bona fide museum, but it felt as casual and unassuming as an open house. His painstaking restoration was a labor of love: He didn’t even charge admission, simply leaving out a donation jar in the courtyard. He turned out to be friendly, talkative, and very knowledgeable about Maltese history and culture. His name was Charlie Bugeja.

Charlie Bugeja’s Siculo-Norman house, parts of which dated back to the Battle of Hastings, was as memorable as anything we saw in Malta. And Charlie’s easy demeanor, a blend of kindness and no-nonsense directness, made it still more memorable.

Charlie Bugeja in front of his house.

During our regrettably short stay we did not have that many encounters with Maltese people, but the few we had (other than with the Cerberus-like bus driver) were invariably warm, friendly and, as best as I could judge, sincere. After I returned home, I learned a little more about how the Maltese held up during the grueling two-year siege to which they were subjected during World War II. In Jellison’s book, he writes, “By their very temperament the Maltese seemed ill prepared for the war ahead. Despite the pressures caused by their modest means, or perhaps because of them, they were uncommonly considerate and good-natured. When crossed, they could be peevish and sometimes slow to forgive, but the idea of committing an act of violence against a fellow human was almost beyond their comprehension. More than that: in keeping with their religious beliefs, they went out of their way to show kindness to others, not only to family and friends but to outsiders as well. The loving attention paid to the children, the consideration and respect given the elderly and infirm, the generous spirit of cooperation among neighbors and even strangers—all bespoke a high degree of civility and human warmth. Once the initial shock of battle had passed, these qualities would assert themselves and serve the Maltese people well during the hard days ahead.”

World War II was a long time ago. But cultural traits are bred in the bone. And there is no reason to think Jellison’s words do not apply to the Maltese people today.

A Valletta street, and the view towards Marsamxett Harbour from Ft. St. Elmo’s.

By the time we left Valletta, our initial sense of its strangeness had begun to fade. This always happens. Traveling is like life: you start out marveling at everything, then you get used to it and everything becomes normal. That’s an inescapable part of the human condition. We move through a world whose mysteries are covered by familiarity, like a painted-over stained-glass window. But there are ways of finding new windows, or scraping the paint off old ones, and one of those ways is travel. For me, Valletta was a new window, a glowing pane of colored glass I’d never seen before. And even after I got used to it, it retained an irreducible element of strangeness. Perhaps that strangeness was innate to it, or perhaps I had simply scraped some paint off my mental window. Or both.

I hope to return to Malta some day. But whether I do or not, for me Valletta will always remain the mysterious, enchanting, decrepit, unfathomable city it was when I first saw it. A gift from the wide, wide world.

You're the 3rd friend in the last 2 weeks who went to Malta and adored it. Your "diary" though is prize winning and I hope you submit it to travel magazines and the Visitors Bureau there - you deserve accolades a-plenty.