Hi. The following piece is adapted from a talk I gave in November at San Francisco’s Aquatic Park Bathhouse (now the Maritime Museum in San Franciso’s National Maritime Historic Park) to celebrate the 90th anniversary of the New Deal. Also speaking were the estimable historian and essayist Heather Cox Richardson and historian and Living New Deal founder Gray Brechin. This piece is free to everyone, but my subsequent, and also all original, pieces on San Francisco history (which will appear under the title “Portals of the Past”) will only be available to subscribers to Kamiya Unlimited.

The New Deal was a shining and unique moment in American history, as close as this nation has ever come to northern European-style socialism. And it’s fitting that two of the most glorious manifestations of that mighty communitarian effort, Aquatic Park and its Bathhouse, are located in one of the most liberal cities in the country, San Francisco. These two urban gems are truly the crown jewels of the New Deal. Without Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration, created during the worst economic crisis in our nation’s history, neither this beautiful cove nor this extraordinary building would exist. It’s hard to think of another site that so beautifully embodies the ideals of that era.

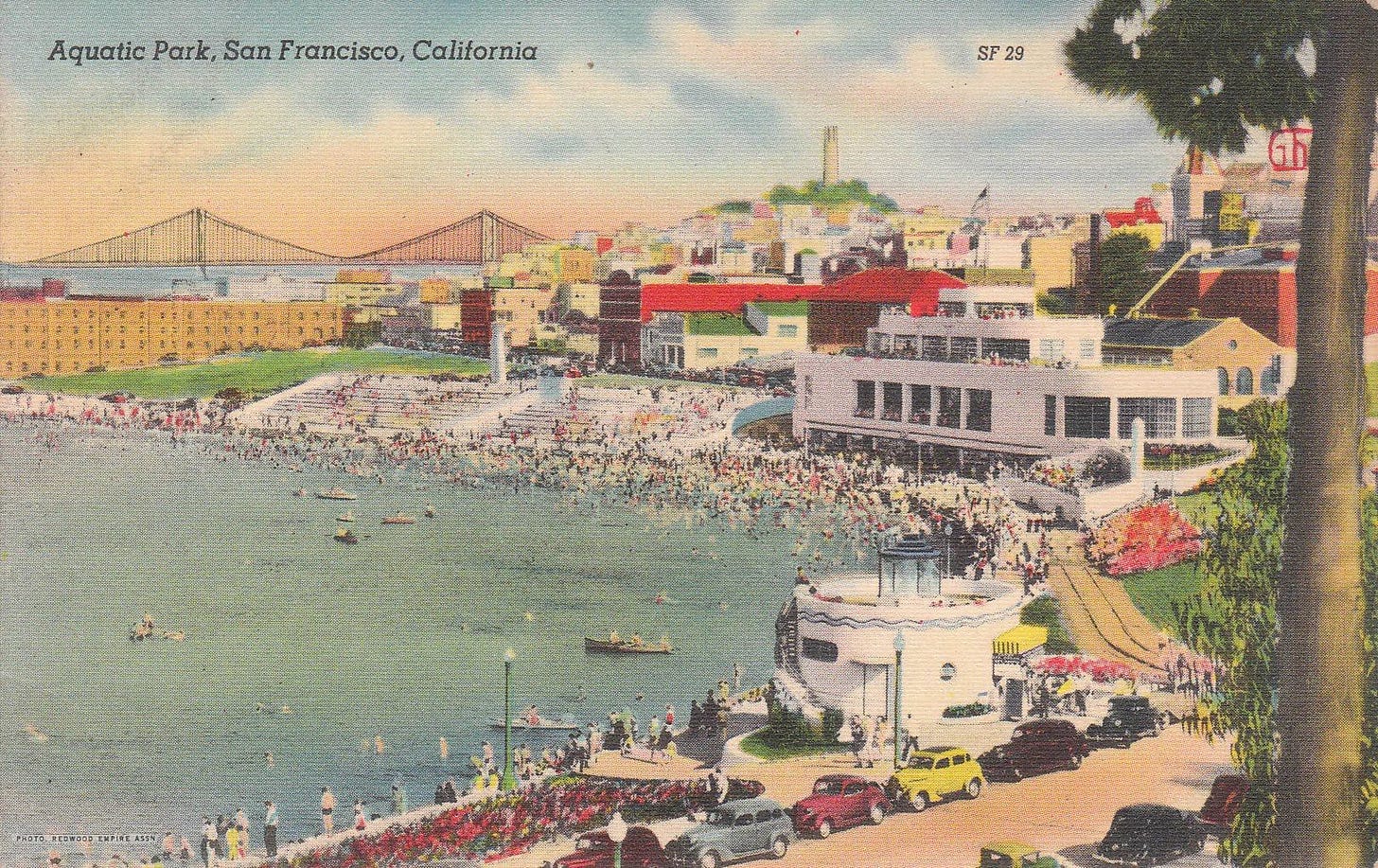

Aquatic Park is one of the most magical beaches to be found in any city in the world, a sandy Shangri-la in the very heart of the city. With all due respect to the “beaches” Paris created along the Seine, no one has gone swimming in that river since Jeanne Moreau leaped into it in Jules and Jim. San Franciscans swim at the foot of Hyde Street every day. But this wondrous little cove under the bluffs was constantly threatened by powerful business interests, and repeatedly trashed by the city. It took an intervention by the federal government, with the crucial help of three venerable aquatic clubs, to preserve San Francisco’s beloved swimming hole and create the park and bathhouse, now the Maritime Museum, that the public enjoys today.

People have always been drawn to this site. Native Americans lived in seasonal camps in the vicinity; native remains were found on a small bluff above the site of the Buena Vista café, their owners possibly expiring of despair after realizing that Irish Coffee would not be invented for several millennia. During the Gold Rush, some Argonauts willing to trade a long walk into town for a beachfront residence erected two dozen buildings near the shoreline.

But as early as the 1860s, trouble, in the form of heavy industry, appeared on the scene. Until well into the 20th century, San Franciscans basically treated the Bay as a giant toilet, and businessmen regarded the remote cove as a perfect place to flush waste material. Two large factories opened here, the Pioneer Woolen Mills and Selby Smelters. But the cove had also become a popular bathing spot, adorned by several swimming houses. In the late 19th and early 20th century, the cove’s two most venerable, beloved, and eternally bickering tenants, the South End Rowing Club and the Dolphin Club, moved here – the former transported by barge in 1908 after the State Board of Harbor Commissioners kicked it out of its home in Mission Bay. The two clubs sat like feuding siblings at the foot of Van Ness, near the present-day Sea Scout building. Another now-defunct swimming club called Ariel also had a clubhouse on the beach.

These three clubs were to play a significant role in saving Aquatic Park.

It may seem odd that a trio of swimming clubs could stand up to big business and City Hall-- powers that almost invariably got their way in 19th century San Francisco. But these clubs punched—or splashed—far above their weight. Competitive water sports of all kinds were far more popular in the 19th and early 20th century than they are now. There was even a brief mania for something called “International tug of war.” Still, the interests of swimmers, rowers, divers and international tug-of-war practitioners, and the existence of an exquisite little beach 25 minutes’ walk from the Montgomery Block at Washington and Montgomery streets, did not impress the city’s commercial interests, who had hitherto successfully monetized every square foot of waterfront land they coveted. Their latest scalp had been Mission Bay, the place from which the South End Club had been unceremoniously booted. Mission Bay was once a 260-acre wonderland of marshes and waterfowl. But it was bisected by a long bridge, poetically named Long Bridge, and then inexorably filled in, and was under the control of the all-powerful Southern Pacific Railroad, aka the “Octopus.” With Mission Bay converted to lucrative landfill, the Octopus and other powerful interests reached their tentacles towards the northern waterfront.

San Francisco officials potentially stood in the Octopus’s way, but City Hall was itself not exactly a paragon of environmental enlightenment. The authorities’ heedless attitude towards the cove was demonstrated after the 1906 earthquake and fire, when the city used it as a dumping ground for vast quantities of debris from downtown. 15,000 truckloads of red brick rubble from the destroyed Palace Hotel, along with debris from Chinatown, “utterly ruined the fine bathing beach,” as the press reported.

This profanation of the cove gave new energy to a longstanding movement, first voiced by famed landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, to turn it into a park. The three swimming clubs formed the Aquatic Park Improvement Organization in 1909 and began lobbying for a park. They staged an Aquatic Park Days, a festival whose diving, swimming and rowing contests drew big crowds.

The press supported the idea of the park, but the business interests appeared to have the upper hand. Developers coveted the land, and the Southern Pacific wanted to fill in the cove to build piers for its steamers. The State Board of Harbor Commissioners was also eager to get rid of the cove: As a first step, it approved a 1914 extension of the State Belt Line railroad, creating a trestle that ran above the water, cutting through the cove the same way that Long Bridge bisected Mission Bay. The Harbor Commission applied to the Board of Supervisors for permission to fill in the entire cove. Meanwhile, the city continued to dump massive amounts of debris on the beach, covering it up yet again and filling in some of the water.

But public outcry swayed the board of supervisors, who listened to their outraged constituents and refused to allow the State Harbor Board and the Octopus to do to the northern waterfront what they had done to Mission Bay. In 1917 the city acquired part of the site from the Southern Pacific in a trade, receiving an additional $390,000 to use in building the park. But the city still had inadequate funding for the major work needed. And the citizens, alas, failed to put their money where their mouth was: bond issues for the park were defeated in 1928 and 1932.

Nonetheless, the city began work on the park. Construction of the Municipal Pier started in 1931. By 1933, the pier was its full 1850 feet long. (Those 1850 feet have inaccessible to the public since October 2022, when the National Park Service decreed that a small earthquake had rendered the pier unsafe. This sad situation calls out for a reborn WPA—or the contemporary equivalent to which we have sadly been reduced, a civic-minded gazillionaire—to step in and save it.) But by 1934, in the depths of the Great Depression, the decades-old dream of a public beach and park at the foot of Hyde Street was in danger of dying. City and state money had dried up. The city had to borrow money and even tools to continue. The project limped along for two years, using private donations of equipment.

But the city had one last card to play. In the summer of 1935, assistant engineer Clyde Healy traveled to Washington, D.C. to ask a newly-founded federal agency called the Works Progress Administration for help.

The Works Progress Administration (later renamed the Works Project Administration) had been created by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to provide jobs for millions of unemployed Americans. The largest New Deal program, its initial appropriation was for $4.9 billion – a staggering 6.7 percent of the nation’s GDP. WPA workers constructed roads, bridges and other public projects in almost every community in the country. San Francisco would be no exception. The agency approved Healey’s request and committed $1.78 million for the job. Along with the Zoo, Aquatic Park would be the most important of the many public projects carried out by the WPA in San Francisco.

The work began in early 1936, when 782 WPA workers arrived at the waterfront site. This force consisted of 9 supervisory engineers and inspectors, 36 labor foremen, 284 skilled and intermediate workers, 453 common laborers, and a full team of artists and sculptors. The day that battalion of federally-paid workers arrived at this cove 87 years ago, shovels and blueprints and paintbrushes in hand, is one of those little-known but indelible moments in the city’s history. I think of it as San Francisco’s D-Day—Democracy Day. There is no painting that records the landing of that motley people’s army, but the great frescoes at Coit Tower, another sublime result of the New Deal, capture its spirit.

The signature structure of the park was arguably one of the greatest buildings in San Francisco, and inarguably the most light-hearted—the Bathhouse, designed by official city architect William Mooser, Jr. His Streamline Moderne masterpiece looks like a luxury liner, right down to the portholes and funnels, forever about to set sail for some happy destination. In the bleak 1930s, the Bathhouse was a joyous note.

The art commissioned to adorn the interior and exterior of the Bathhouse is just as memorable as the building itself. The artists were hired by the Federal Art Project and paid about $96 a month—just enough to live on. They were a remarkable crew, and none more fascinating than the man tapped to head the project, a Minnesota-born artist named Hilaire Hiler. To say Hiler was a multifaceted man would be like saying Leonard da Vinci showed a bit of promise. In the 1920s Hiler had run a legendary Paris nightclub called the Jockey Club, where he played jazz piano and rubbed shoulders with the avant-garde likes of Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp. He also studied psychoanalysis with Otto Rank, one of Freud’s closest colleagues, and developed a brilliantly idiosyncratic philosophy of color, exemplified in the circular ceiling work in the Bathhouse he called the “Prismatarium.” Hiler hired the talented and egotistical sculptor Benjamin Bufano, the pioneering African-American mosaic artist Sargent Johnson, gifted muralist Richard Ayer, and others.

What’s notable about the art in the Bathhouse is that it is abstract, dreamlike and formalist, reminiscent of European avant-gardists like Vassily Kandinsky or Yves Tanguy. Actually, Hiler’s murals go beyond Kandinsky—they look like Spongebob Squarepants on psycilocybin. Its modernism sets it apart from the vast majority of WPA-funded art across the United States, which exemplifies a genre called “American Scene Painting,” figurative, broad-shouldered celebrations of the American heartland. The aforementioned murals at Coit Tower are classic examples of this dominant WPA style, albeit with a more left-wing slant than most thanks largely to the influence of the Mexican Communist artist Diego Rivera, who had executed two commissions in San Francisco in 1930. Indeed, a controversy over two explicitly pro-Communist murals at Coit Tower led officials to paint over the Tower’s windows, delay the opening, and finally paint over the offending images.

The artists who created the works in the Bathhouse made no such political statements in their work. But they, too, became deeply involved in a raging controversy, one that was ultimately just as political as the Coit Tower battle.

Aquatic Park was dedicated on January 22, 1939, in front of massive crowds. But trouble had been bubbling up behind the portholes for more than a year, and it boiled over just before the opening, when Hiler angrily resigned. Artists Benny Bufano, Sargent Johnson and Richard Ayer also walked off the job.

The artists’ resignations were the result of a yawning chasm between their idealistic vision of the Bathhouse as a public amenity, a vision shared by the WPA, and the crasser reality of the Bathhouse once the city began to actually operate it. The WPA paid for 99% of the Bathhouse, but it had always planned to turn it over to the city—and the city, which was broke, lacked the resources to run it. So to raise revenue, in 1938 the city brought in two restaurateurs, brothers Leo and Kenneth Gordon, who set about turning the building into a bar, nightclub and restaurant called the Aquatic Park Casino. (There was no gambling at the Casino, just drinking, dancing and carousing). The Gordons convinced city officials to make major changes to the building’s interior, including turning an open area on the third floor, which was supposed to be a public lounge, into a banquet hall, and adding orange and green cocktail furniture and what Hiler termed a “large and horrendous clock.” All of these changes were made without Hiler’s consent. For a man whose sensitivity to color verged on the maniacal, the sudden appearance of orange and green cocktail furniture in his spectral sanctum sanctorum must have been like being a curator at the Met and discovering that all the Vermeers had been replaced overnight with Thomas Kincaids.

The WPA wasn’t happy, either. Irritated by the slow pace of work and the concession given to the Gordons, WPA officials ended their participation in the project early, meaning the Bathhouse and park was unfinished when it opened.

Despite the fact it was unfinished, despite the fact the beaches had not yet received sand, and despite the sturm und drang behind the scenes, the park was initially a big success, with thousands flocking to the beach to enjoy a swim in the bay. And during its brief life the Aquatic Park Casino seems to have been a jumping joint. A photograph displayed at the Bathhouse shows legendary San Francisco jazz bassist Vernon Alley playing in front of a large and enthusiastic crowd. But soon both the public and the press became increasingly dissatisfied with the way the Bathhouse was being run—and once again, the villains were the Gordons.

In the egalitarian spirit of the times, the city and the WPA had described the Bathhouse as a “Palace for the Public.” Perhaps any concessionaire would have had trouble living up to that billing while still making the Bathhouse a going concern, but the Gordons were egregiously awful tenants. They set prices so high that most patrons were discouraged, and they treated the public in a heavy-handed and exclusionary manner. On one occasion, a WPA investigator observed a group of school boys bringing their lunches to the open veranda overlooking the cove. "They were ordered to leave by the concessioner," the investigator reported.

And as we’ve seen, the conversion of a people’s palace into a private casino did not sit well with the artists. In April 1939 Benjamin Bufano wrote a letter to the WPA administration, stating he would not allow his 14 sculptures to be displayed because the project had deteriorated into a private enterprise. The Chronicle quoted the “shaggy-maned sculptor” as saying the average person was “placed in an embarrassing position if he does not purchase refreshments while passing through,” and “the very people for whom the center was created are discouraged.” Sargent Johnson and Richard Ayer also resigned in protest, Johnson leaving his 140-foot veranda mosaic unfinished, as it is to this day.

So while the art in the Bathhouse may be formalist, dreamlike, and peaceful, the artists who created it shared the same public-spirited vision, and politics, as their colleagues who had worked on Coit Tower five years earlier.

Public indignation soon led the city to throw out the Gordon Brothers. And after many other only-in-San-Francisco twists and turns—including the creation of a beach using sand from the excavation of the Union Square Parking Garage, and the vision and zeal of Karl Kortum, the father of what is now the San Francisco Maritime National Historic Park —Aquatic Park and its wonderful Bathhouse finally became the public treasures they were always intended to be, joyous and enduring monuments to that shining moment in America’s darkest hour, the New Deal.

Thank you for your ongoing work! You may know that another jewel of the New Deal, Diego Rivera’s “Pan American Unity” is going back into storage. The reasons why remain obscure. Interested? Write Jeff at jgoldtho@ccsf.edu